We long to have a home where civil freedoms are respected, where our children will not be subject to mass surveillance, abuse of human rights, political censorship and mass incarceration. We stand with all the free peoples of the world and hope you stand with us in our quest for justice and freedom.

In 2010, the Chief Executive Donald Tsang required students to adopt communist ideals disguised as "moral education".

Joshua Wong, an ordinary student, decided it was time to take action. He used various social media platforms to spread the ideas of Scholarism, a student-led democracy group that he founded to get rid of the education bill.

He gained traction with the Scholarism group, eventually discussing the education policy with lawmakers and government officials.

Unfortunately, the problem became worse in 2012 when Tsang was succeeded by CY Leung, who was rumored to be a Communist Party member. Leung required the use of a manual in primary schools, that badmouthed Western democracy and US-style bipartisan politics.

But Scholarism, Joshua Wong, and a network of other activists were determined to fight for their future. They led an initial protest, but it didn't change Leung's mind. After a number of attempts, they decided to pick up their efforts: they led a hunger-strike, ramped up recruitment, and gained more media exposure.

This final push worked, because after nine days of determined protest with over 120,000 people, Leung finally got rid of his propaganda curriculum.

What some might call a small success was actually incredibly energizing to the pan-democracy movement fledgling in Hong Kong. The last such organized political success was in 2003, when protestors got rid of a security bill. Thus, students were more inspired than ever to actively participate in politics. However, the fight was far from over.

In 2013, Benny Tai, a constitutional law expert, teamed up with some other academics to determine how Hong Kongers could actually get to vote for the Chief Executive, instead of it having chosen by a Chinese committee.

In 2007, the NPC (Standing Committee of the National People's Congress) promised universal suffrage for Hong Kong: in other words, they guaranteed that Hong Kong could vote for their Chief Executive, and all members of the legislative branch (aka LegCo or Legislative Council) by 2017 and 2020, respectively. Of course, Tai and his colleagues were suspicious of this claim, and accordingly prepared for the worst scenario, in which China would refuse to follow through on its promises.

What they came up with was Occupy Central with Love and Peace, a movement that threatened China that it would participate in civil disobedience if the government did not keep its promise. This was a threat to China because their economy would slow down if people stopped going to work and doing other sorts of strikes.

As a result of these initial efforts, China granted Hong Kong a strange, twisted version of "universal suffrage". They limited the number of candidates that Hong Kong could vote for by requiring that each candidate be approved by a 1,200 person committee consisting of mainland Chinese. Obviously, this was not enough. The stage was set for a mass revolution, with the people of Hong Kong angered from years of political mistreatment.

The citizens marched in the streets, holding umbrellas, and participated in a mass form of peaceful protest for universal suffrage. The umbrellas were for blocking pepper spray and other types of anti-protest measures used by police. It was quite a sight, as Hong Kong people are traditionally viewed as individualistic, but the movement united them. They were all there with the common purpose of demanding democratic elections.

Ultimately, the Umbrella Movement failed, but it was amazing. It was 79 days of protest, day and night, with thousands of people on the streets. It showed just what was possible with collective activism. It also put Hong Kong on the international stage, with the world watching the fight for democracy.

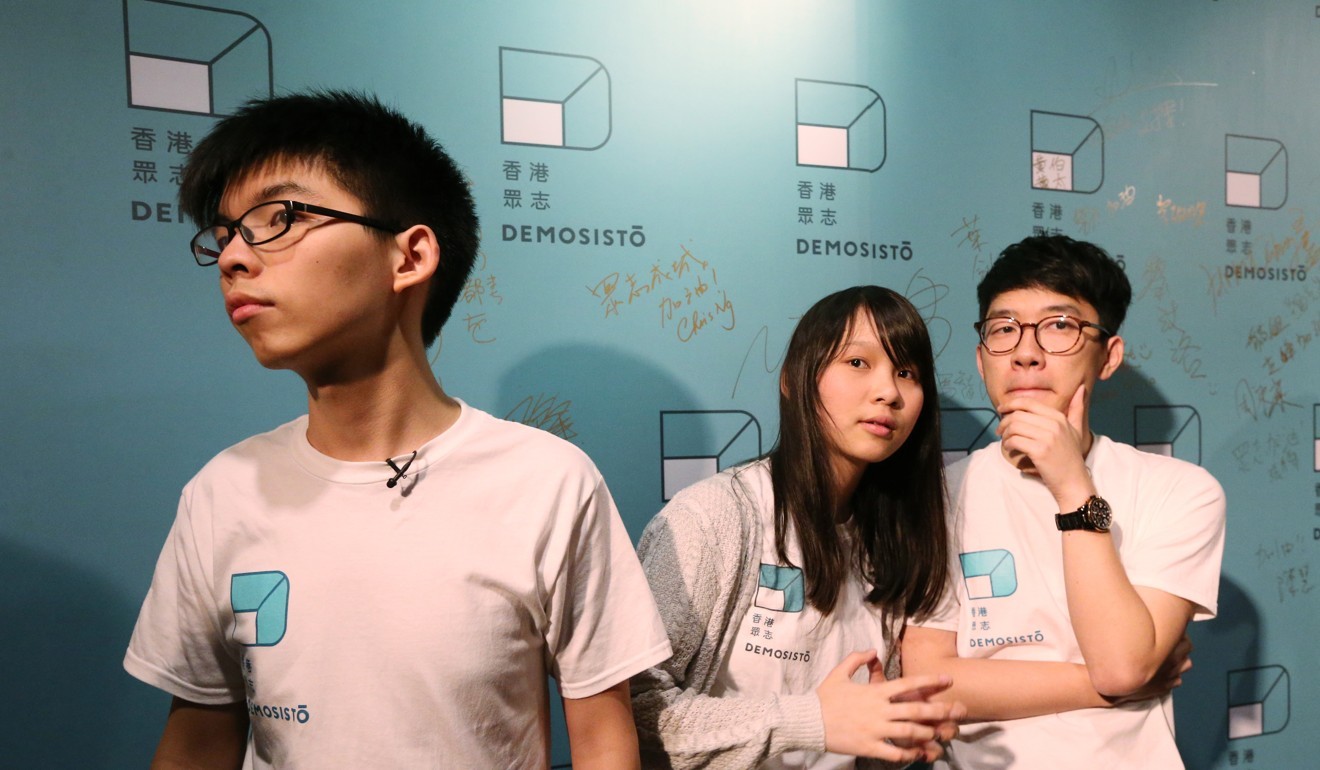

Joshua Wong decided after the Umbrella Movement loss that simply becoming angry and protesting had no effect on the political system. Thus, he founded Demosisto with peers, which was an organization that aimed to get pro-democratic candidates to join the government and influence policies instead of simply protesting.

But at the same time these pan-democracy candidates were elected into office, China became less and less patient. The Chinese government began removing books, jailing activists, and so on. Additionally, not very many businessmen nor educated people voted for the Demosisto party, beacuse they were generally conservative. And even after the Demosisto candidates were voted into the LegCo, they were kicked out by China for mis-speaking an oath.

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy supporters have reached a tipping point in the fight against authoritarian rule, participating in protests and other forms of activism in unprecedented numbers. As a result of China’s overreach into Hong Kong, the citizens have been kept from having an independent judiciary, freedom of press and expression, and fully democratic elections.

In 2019, Carrie Lam, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, made a law that makes it possible for convicted Hong Kong criminals to be tried in mainland China. After some initial protests, the government suspended the bill, but did not remove it completely; this led to more anger among citizens, and was essentially the tipping point for Hong Kong. As a result, millions of people started protesting for the much broader goal of universal suffrage and general freedom.

The situation was so intense at one point that the people of Hong Kong, once dubbed by the media as being some of the world’s most polite protestors, have resorted to methods of violence such as smashing the LegCo building and battering the police and any suspected undercover cops. Such violence has two main causes. Firstly, the youth – the generation that will inherit Hong Kong and its governance – feel that this is the absolute last chance to subvert the authoritarian overreach by China. And secondly, a large portion of the protestors believe that peaceful actions achieve nothing. Vandals spray-painted inside the Legislative Council building: “It was you who taught us peaceful protest doesn’t work”. Nevertheless, the radical and peaceful wings stayed united.

On the front lines of the protest, Molotov cocktails burnt in the streets, bricks were thrown left and right, and lasers were used to distract police. The movement evacuated every day to minimize arrests.

Violence was common; on August 11th, a woman lost her eye due to police and tear gas use. Police brutally beat up protestors with sticks, and shot paintball guns at point black range. As a result, the people lost trust in the police and fought against the police on August 12, 2019. Protestors shut down the airport, to induce pressure on the government to stop the brutality. Suspected undercover cops were beaten and kept from medical treatment, much like a witch-hunt.

The duality of impact that the protests have is interesting; from Hong Kong's perspective, it's a good thing that the protests could inspire similar ones in the mainland, but China obviously wouldn't want that.

Additionally, many Hong Kongers felt like this was their last chance to make a change; several high profile activists were arrested, and police brutality hit new records. Because people were so desperate, millions of diverse people were a part of the movement - the elderly, lawyers, the medical community, civil servants, teachers, and the youth.

Similar to the Umbrella Movement, the extradition protest escalated to having a much larger and serious goal than just opposing the extradition law. They wanted universal suffrage and the ability to make autonomous decisions regarding government and policy.

Some important questions naturally arise upon considering this violence of Hong Kong’s 2019 resistance, not the least of which is the following: is violence necessary to achieve Hong Kong’s democracy? When the activists broke into the Legislative Council, even pro-democracy citizens started doubting their actions. Fernando Cheung, a pro-democracy politician, says that the break-in absolutely should not have happened, because “any type of violence like that, even though they were not directed to any person, it may make the movement lose its momentum and public support”.

Another important question is: can the democracy advocates possibly hope to achieve universal suffrage at this rate, given that China’s thirst for power has pushed them to crack down on activists, censor books and information, suppress the autonomy and fundamental human rights of its own citizens, not to mention use unprecedented amounts of police brutality?